Synaesthesia and Orphism

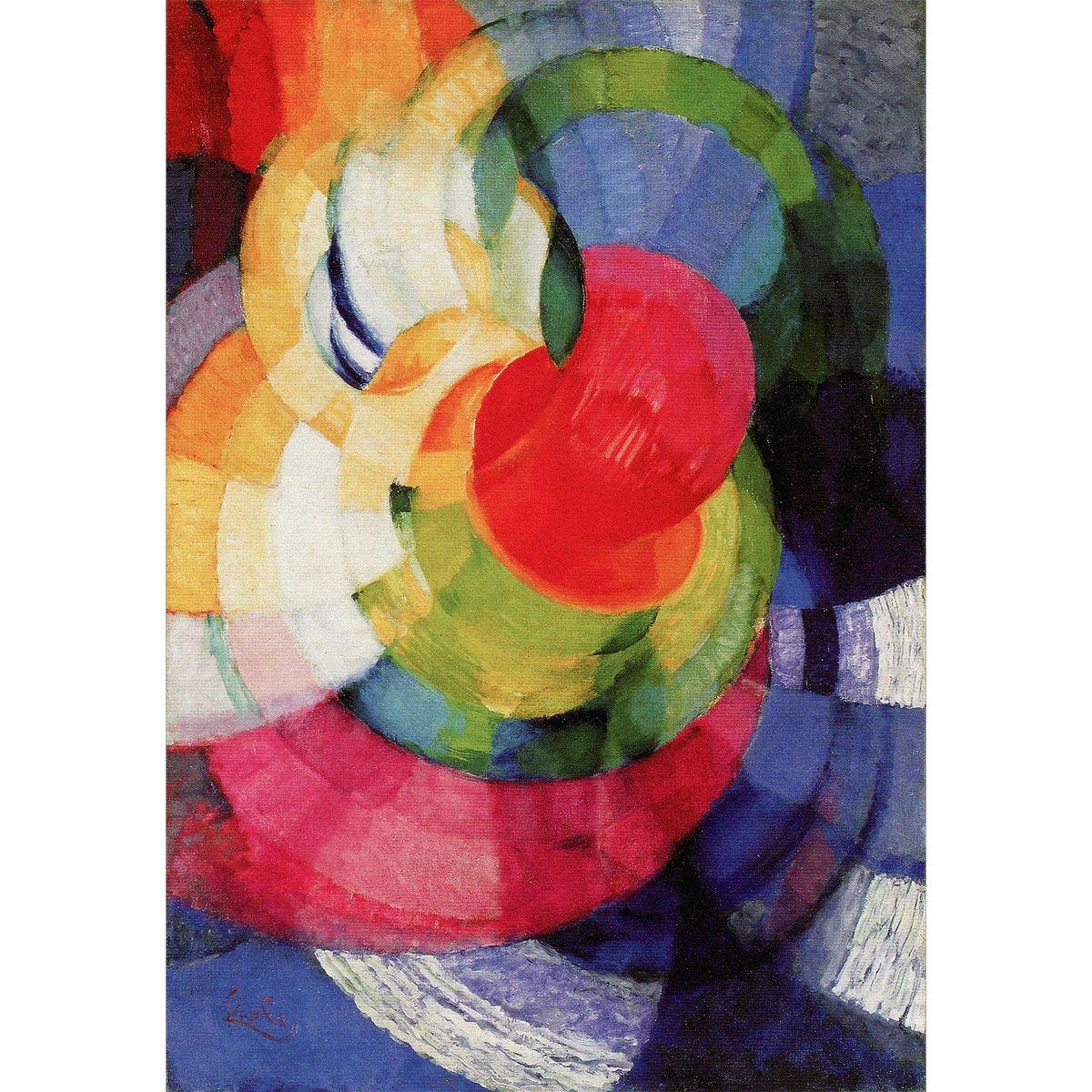

Artists concerned with music in the early 20th century were familiar with the phenomenon of synaesthesia. The phenomenon promotes the idea that analogies between different senses can be broken down into specific correlations. Kandinsky famously wrote in On the Spiritual in Art, that “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings”. This book was a pioneering doctrine in the creative application of synaesthesia. The effect that colour could have on a person on a deeper level, he states is down to the sensitivity of the person. A sensitive soul will respond to the “spiritual vibrations” of the colour, and this is their psychic effect. This psychic effect is described in a manner analogous with synaesthesia, for instance, a red evoking a sense of heat like flame or disgust as from blood. This theme is developed further in his discussion of ‘scented colours’ and the ‘sound of colours’. In discussing abstraction, Kandinsky writes that the true harmony of a form “exercises a direct impression on the soul”, and that this emotion is not directly related to any specific object but is inexplicable. His work, Composition VII (1913) is evocative of the chaos of undeterminable and incoherent sensual experience.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, (1913), oil on canvas.

The vortex of interlocking colour is not expressive of a particular musical structure but of a dissonant harmony to create ‘pure’ abstract painting. Kandinsky was fascinated by theosophy, a spiritual movement introduced by Madame Helene Blavatsky, which sought to find inner knowledge and an ‘eternal truth’. Kandinsky believed that intense sensual experiences could spark a spiritual awakening and the ability to gain new consciousnesses. Therefore, engaging more senses through generating musical artwork, was a spiritual practise, which made musical art, spiritual art.

Spiritualism was also a vehicle to abstraction for František Kupka, one of the figureheads of the Orphism movement. He studied in Vienna from 1892, where he was introduced to theosophy. He later became a spiritual medium to generate extra income in Prague. For him, music was a vehicle to access a higher state of consciousness, through connection to its immaterial essence. Kupka said in advocacy of synaesthesia, “The public need to add to the action of the optic nerve those of the olfactory, acoustic and sensory ones...I believe I can find something between sight and hearing, and I can produce a fugue in colours, as Bach has done in music.” He even labelled himself in a letter from Paris to his friend, as a ‘‘colour symphonist’’. He sought to make what was intangible, visible through non-representational art from music.

The eighteenth-century philosopher, Goethe, believed that colour defined the foundational explanation for all metamorphic or active processes of nature. To him, colours are an active component of this world of flux. Goethe criticised Newton’s study of light as static entities, believing that his mathematical studies excluded the world’s wholistic interactions. He progressed Newton’s foundational theories by studying perception and the relationship between colour and its and observers. In Chromatic Circle (1809) Goethe addresses ‘natural’ implications of colours. Purple, at the top, is symbolic of majesty. Refreshing yellow is representative of sunlight, and blue evokes the tranquillity of the ocean. The relationship between the colours is shown by their adjacent positions on the wheel all of which intermix to create new colours.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Chromatic Circle, (1809), watercolour on paper.

Additionally, one of Goethe’s other colour wheels titled Allegorical, Symbolic, Mystic use of Colour (1799), directly addresses colour psychology and labels colours with human qualities. Red is "beautiful", orange "noble", yellow "good", green "useful", blue "common", and violet "unnecessary". Therefore, Goethe drew on the notions of synaesthesia before they were fully realised in the 1880s, believing that colour could stimulate a range of associations and sensory reactions.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Allegorical, Symbolic, Mystic use of Colour, (1799), watercolour and ink on paper.

Kupka explored the properties of colours, researching colour theory and colour wheels such as Isaac Newton’s (c.1880) and Goethe’s wheels. Newton wrote: "As the harmony and discord of sounds proceed from the properties of the aerial vibrations, so may the harmony of certain colours ... and the discord of others ... proceed from the properties of the aethereal.” Newton divided the optical spectrum into seven parts and paired each with the musical scale. The title Disc of Newton (1912) by Kupka, is a direct reference to Newton’s theory of colour.

František Kupka, Disc of Newton,( 1912), oil on canvas.

The inclusion of musical terminology in the full title implies that the colour experimentation is representative of more than just dynamism, but also evokes sonoric elements; the colours are likely to have musical significance and meaning. In the painting, the sun is represented as a vivid red circle, broken into fragments. Kupka’s cosmological interests suggest these could be planets, with the expanding forms surrounding them, their orbits. The colours appear alive with dynamism, with their blending and morphing enhancing this velocity. He has potentially taken on Goethe’s understanding of colour theory which prioritises movement.

The alternative title for Orphism was ‘Simultanism’, which highlights the importance of movement and inter-formal interactions. Robert Delaunay, another leading member of the movement, wrote to Kandinsky in 1912, stating, “the laws I have discovered...are based on research into the transparency of colour, that can be compared with musical tones. This has obliged me to discover the movement of colours”. Thus, he is using music as a vehicle to explore colour-dynamics in a similar fashion to Kupka. In 1912 in the Essay on Light, Delaunay continued this notion further, writing that colour-movement is stimulated by the unequal measures which constitute reality: “This reality has depth (we see as far as the stars), and thus becomes rhythmic Simultaneity”. He is focused on the complimentary contrast of colours and the resulting effect. Delaunay’s Rhythm (1912) is divided into two panels which together create a square image. Like in Kupka’s Disc of Newton, the dominating spheres are circled by radiating rings, invigorating the forms with a sense of movement. Moreover, the forms are intersected by the break in the canvas, which off-sets the predictability of the spherical movements. One can see the vivid use of colour in contrasting forms, but not as an exercise to produce harmonic, musical effects, but to use the complimentary and juxtaposing essence of the colour as a vehicle to enhance the rhythm.

Robert Delaunay, Rhythm, (1912), oil on canvas.

Kandinsky’s influence in the field of synaesthesia cannot be underestimated in the discourse of ‘visual music’. Although Delaunay and Kupka used musical terms in their titles, none of the explored paintings directly reference a type of music in a literal translation. The artists were interested in the general musicality of this form of abstraction and use ‘explicit thematisations’ to signpost intermedial relationships and analogies. For instance, the tonality and combinations of specific colours, can be compared with a major or minor key and related moods or arrangements of repeated forms with certain rhythms. These innovations in painting suggest a sense of experimentation as theoretical exercises to pursue the new avenue of musicalised art. The following chapters explore the development of these concepts into recognisable musical structures.

Although Kandinsky undoubtedly influenced the work of Orphic painters, there is not enough evidence that specifically synaesthetic experiences had been involved in the process, beyond just instinctive associations between colour, form and music. Many question whether Kandisnky even had synaesthesia, or was simply just fascinated by the condition. It was certainly beneficial to his career to assert himself as a synaesthetic person to his colleagues and customers, but there is no medical proof that he was himself coloured by the condition...

Bibliography:

Brougher, Kerry; Strick, Jeremy; Wiseman, Ari, Visual Music, New York: Thames & Hudson 2005.

Gage, John, Colour and Meaning: Art, Science and Symbolism, California: University of California Press, 1999.

Shaw-Miller, Simon, Visible Deeds of Music. Art and Music from Wagner to Cage, New Haven, and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Point and Line to Plane, trans. by Howard Dearstyne and Hilla Rebay, New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1979.

Kandinsky, Wassily, Sounds, trans. by Elizabeth R. Napier, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.